The Tripartite Paradigm: Architecting Enterprise AI Solutions by Orchestrating Software 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0

The modern enterprise is navigating a profound transformation in how computational systems are conceived, built, and deployed. This shift, often framed as the evolution from Software 1.0 through Software 3.0, demands that architects discard the notion of a singular programming paradigm and instead embrace a fluent, composite approach. Successful AI architecture is no longer about selecting a single stack but about intelligently orchestrating three distinct methodologies to meet mission-critical requirements for determinism, scale, and intelligence.

I. Strategic Imperative: The End of Monolithic Software Development

A. The Software Evolution Framework: From Explicit Code to Emergent Computation

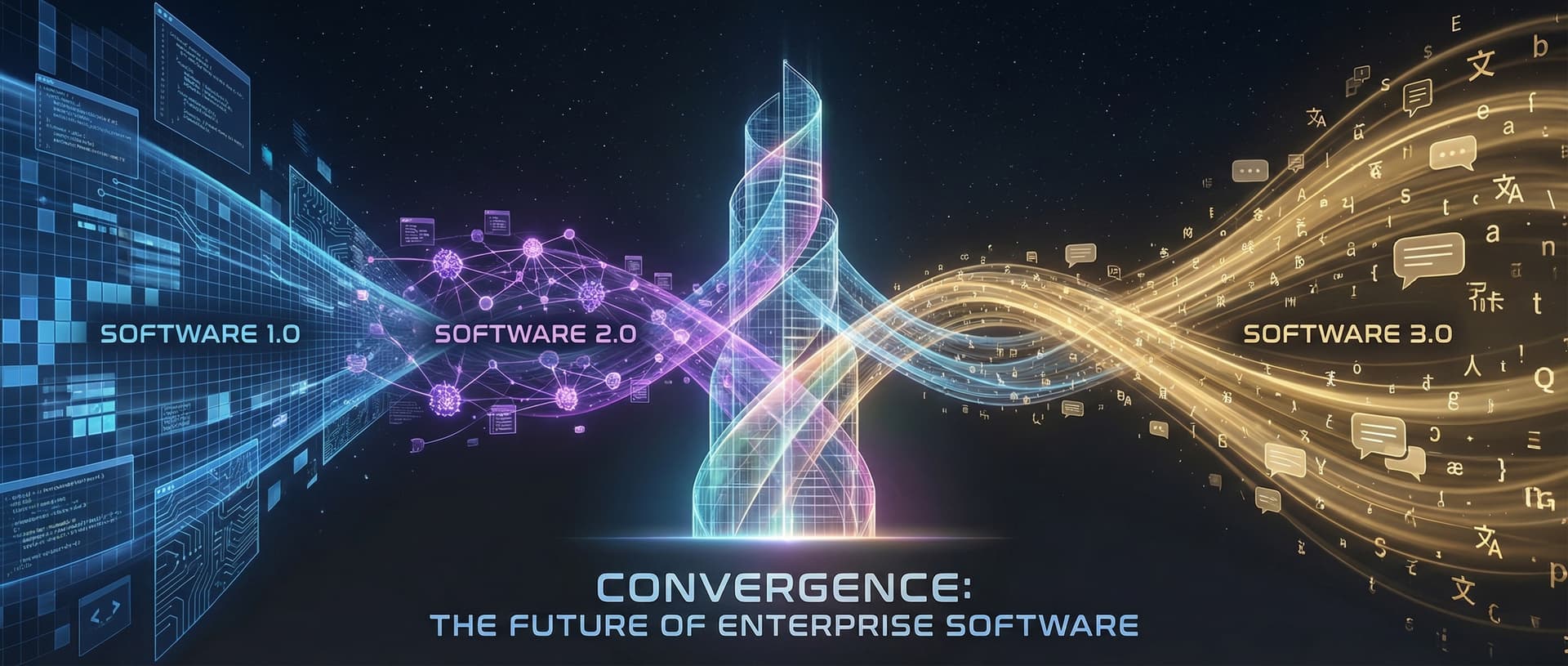

The history of software development can be categorized by how human intent is communicated to the machine, resulting in three concurrent programming paradigms that now define enterprise architecture.

Software 1.0: The Classical Stack (The Artisan Era)

Software 1.0 is the foundation of classical computing, defined by explicit, hand-written instructions in deterministic languages such as C++ or Python. This programming paradigm is characterized by logical flow, absolute human design, and predictability. In the current enterprise landscape, the intrinsic value of Software 1.0 lies not in developing new intelligence, but in providing stability, fixed business logic, I/O handling, and seamless integration with legacy systems. It is the guarantor of control flow and deterministic execution that is required to wrap the subsequent, more volatile paradigms.

Software 2.0: The Neural Network Era (The Industrial Era)

The advent of Software 2.0 introduced a significant abstraction, moving away from explicit instruction toward learned behavior. In this paradigm, the “code” is essentially the weights of a neural network, which are written by optimizers through training on vast datasets. The human role shifted from writing algorithms to curating, labeling, and optimizing the training data. Software 2.0 proved revolutionary for problems characterized by vast, complex solution spaces, enabling breakthroughs in fields like computer vision and specialized predictive analytics. Crucially, Software 2.0 remains indispensable for tasks requiring deterministic performance, cost efficiency, and low latency, such as specialized classification, regression, and anomaly detection, where training a focused model remains superior to a generalized model.

Software 3.0: The LLM/Prompt Era (The Conversational Era)

Software 3.0 represents the latest evolution, centered around Large Language Models (LLMs). The programming medium has shifted again, moving from specialized weights to natural language prompts. The programming language is, in effect, human language. This enables emergent computation, where tasks like analyzing, summarizing, generating content, refactoring code, translating, and critiquing are executed through high-level conversational instruction. The role of the engineer evolves from direct coding or data curating to managing, orchestrating, and guiding these generative systems through context definition. This shift is particularly evident in fields like AI-powered marketing strategy and modern product management, where LLMs are redefining strategic workflows.

B. The Mandate for Architectural Fluency: Orchestration, Not Replacement

The analysis confirms that these three paradigms are distinct methodologies, and enterprise builders must be fluent in all of them to make appropriate architectural decisions. The misconception that newer models (3.0) replace older ones (1.0, 2.0) is fundamentally flawed in mission-critical environments.

The requirement for orchestration becomes evident in complex operational scenarios. Consider an AI-powered customer support system: Software 1.0 is required to retrieve stable legacy system data, such as payment history or connection status; Software 2.0 (or a trained language model component) interprets the user’s request contextually; and Software 3.0 automates high-level actions, such as generating notifications or scheduling service reactivations, based on the interpreted context and retrieved data. This interplay, where 1.0 provides stability, 2.0 offers intelligent adaptation, and 3.0 drives automation, is the definition of the modern, personalized, and efficient enterprise application.

A critical architectural consideration stems from the difference in how these systems operate. Software 1.0 relies on explicit algorithms and predetermined control flow; Software 3.0 relies on emergent computation guided by linguistic prompts.

The Architecture Inversion

This represents an Architecture Inversion, where the focus shifts from meticulously defining rigid data structures and explicit step-by-step logic (1.0) to defining the Context Orchestration Pattern.

The architect’s task is now to manage the dynamic informational environment, including tools, memory, and grounding data, that guides the LLM’s behavior. This is essential for ensuring that the probabilistic “dialogue” of Software 3.0 respects the strict operational, safety, and financial boundaries required of enterprise applications.

Furthermore, the nature of Software 3.0 introduces new systemic risks. LLMs are powerful but inherently probabilistic; they can generalize beyond their training data but also “hallucinate convincingly”.

Socio-Technical Systems

This duality means that Software 3.0 systems are inherently socio-technical. They mandate rigorous engineering combined with continuous human oversight, monitoring of AI outputs, and iterative prompt tuning. The instability inherent in probabilistic outputs must be managed by robust infrastructure, which underscores the necessity of integrated MLOps and governance frameworks.

II. Foundational Architecture: The Composite AI Blueprint

The practical realization of the tripartite paradigm in the enterprise is achieved through Composite AI, a structured approach that integrates the specialized capabilities of each software era.

A. Defining Composite AI: The Integration Strategy

Composite AI is an advanced approach that leverages multiple distinct AI technologies, such as Machine Learning, Natural Language Processing, and traditional rule-based expert systems, to build sophisticated, flexible, and context-aware solutions. This integrated structure offers superior performance and enhanced flexibility by combining the strengths of diverse techniques.

In this model, classical code (Software 1.0) functions as the indispensable wrapper, providing the deterministic, high-level control flow, input/output management, and pre/post-processing logic. This wrapper orchestrates the probabilistic cores (Software 2.0 and 3.0). For instance, in finance, composite AI combines statistical models (2.0), fraud detection logic (1.0), and NLP (3.0) to deliver a holistic system for risk assessment and automated reporting. Similar principles apply to digital commerce optimization, where deterministic business rules wrap probabilistic conversion models.

Layered Explainability for Auditability A key architectural challenge in highly regulated industries is the opacity of large neural networks. To manage this, composite architectures must adopt a layered approach to explainability. This strategy isolates the opaque inference space of the LLM (Software 3.0) from the auditable process space above it. By situating LLM reasoning within formalized decision models, such as Question–Option–Criteria (QOC), Sensitivity Analysis, or Risk Management frameworks (Software 1.0 constructs), the approach transforms otherwise unexplainable outputs into transparent, auditable decision traces. This architectural separation ensures that while complex models are used for reasoning, the ultimate decision-making context and process flow are traceable and compliant.

B. Critical Architectural Trade-offs in Paradigm Selection

Architecting hybrid AI is fundamentally a resource allocation problem, governed by trade-offs between accuracy, latency, size, and cost.

Latency, Size, and Cost Considerations The decision regarding which paradigm to deploy: a massive LLM (Software 3.0), a specialized ML model (Software 2.0), or pure deterministic logic (Software 1.0), hinges significantly on performance requirements. Smaller Language Models (SLMs) in the 1–15 billion parameter range offer significant advantages in latency, often delivering responses in tens of milliseconds compared to hundreds of milliseconds or more for large, cloud-hosted LLMs. These SLMs can rival older LLMs when expertly fine-tuned on domain-specific data, making them ideal for structured or narrow tasks where speed is critical. Conversely, LLMs above 100 billion parameters generally dominate benchmarks for complex, open-ended reasoning and long context windows. The choice must therefore be deliberate: specialization through fine-tuning (SW 2.0 approach applied to LMs) is an architectural tool for meeting strict latency requirements and optimizing cost, especially in user-facing applications where sub-second responses are mandatory.

Inference Scaling as Constrained Optimization Architectural design related to inference must be framed as a constrained optimization problem: minimizing prediction error subject to a fixed compute budget (FLOPs or dollars). The decision space involves key variables: the model size (), the number of tokens generated per request (representing the depth of reasoning, ), and the inference strategy (), which includes techniques like majority voting, tree search, or verifier-in-the-loop mechanisms.

The most efficient solution is frequently not the largest model but the smartest inference strategy. Architects must define the Computational Inference Strategy (CIS) upfront. For complex, mission-critical tasks, the system may employ Software 1.0 logic to trigger verification loops (running the prompt through multiple models or self-correction steps), consciously trading increased latency () for higher accuracy, rather than simply accepting the output of a single, quick model call. Analysis confirms that smaller models, when paired with smarter search or voting strategies, often occupy a superior accuracy-compute Pareto frontier for a given budget, outperforming naive “bigger model” approaches.

Comparative Architectural Trade-offs

III. Architectural Patterns for Software 3.0 Integration

The integration of Software 3.0 capabilities requires specialized architectural patterns to mitigate inherent unpredictability and scale reliably within the enterprise ecosystem. The two predominant patterns are Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Multi-Agent Systems.

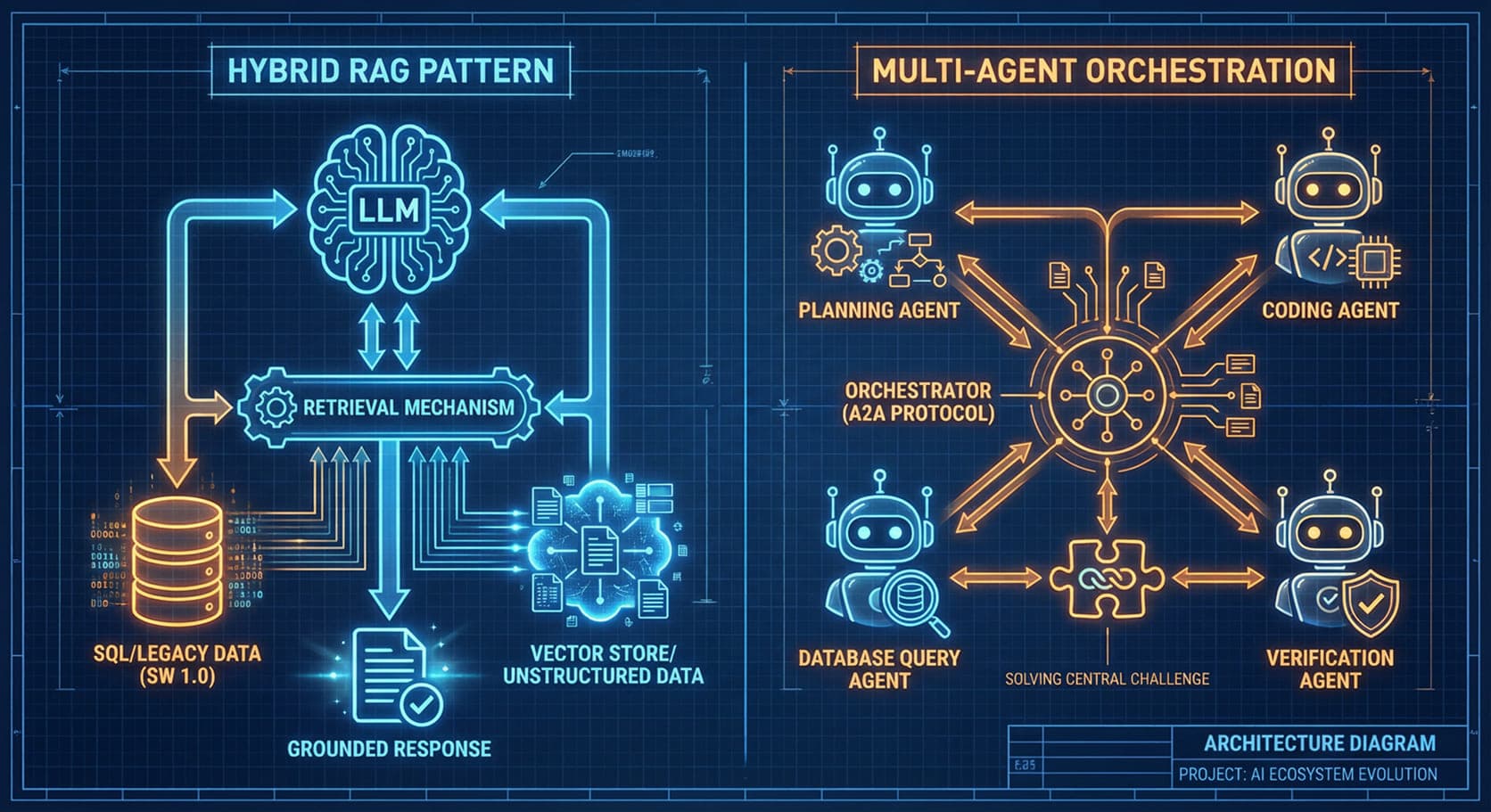

A. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Architecture: The Knowledge Layer

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a foundational architectural pattern that addresses the LLM’s primary limitation: lack of current, proprietary, and specific organizational knowledge. RAG works by injecting trusted, organizational data into the LLM’s context window prior to generation, ensuring outputs are grounded, accurate, and aligned with business insights.

The Necessity of Hybrid RAG Enterprise data is rarely centralized or uniform. It exists across structured databases (often SW 1.0 assets) and unstructured documents, files, and knowledge bases (semantic data). Therefore, the simple, retrieval-first RAG approach is often a bottleneck. Hybrid RAG represents the architectural evolution necessary for the enterprise, where the retrieval mechanism intelligently queries both structured data sources and semantic vector stores. By synthesizing insights from both sources in real-time, hybrid RAG delivers demonstrably superior factual correctness, relevance, and trustworthiness, effectively dissolving the technical and conceptual barriers between structured and unstructured data realms required for complex decision-making.

The effectiveness and safety of RAG are directly proportional to the quality and governance of the underlying data. If the system pulls from historical, sensitive, or poorly managed data, the AI becomes untrustworthy and non-compliant. Therefore, Data Governance is an architectural dependency for RAG systems. Architects must implement rigorous Software 1.0 data practices, including metadata management, data retention policies, anonymization standards, and version control for knowledge graphs. This investment in Trust Infrastructure, ensuring data integrity and provenance tracking, is what guarantees that the probabilistic outputs of Software 3.0 are auditable and grounded, which is non-negotiable for securing business continuity in regulated environments.

B. Multi-Agent Systems: Decomposing Complexity

Moving beyond monolithic architectures (where a single LLM or RAG system handles all functions, creating a single point of failure), the future of intelligent systems lies in decentralized, multi-agent frameworks. This architectural strategy applies the microservice concept (a core Software 1.0 principle) to cognitive workloads.

The Agent2Agent (A2A) Protocol Complex tasks are decomposed and distributed among a network of specialized, autonomous agents. This shift, governed by the Agent2Agent (A2A) protocol, moves from a single, generalist AI to a team of experts, each skilled in a domain (e.g., parsing legal documents, querying a specific database, generating code). A standardized communication layer (the A2A protocol) enables seamless collaboration, leading to systems that are inherently more scalable, resilient, and manageable.

Crucially, while the agents are powered by the emergent capabilities of LLMs (Software 3.0), they require deterministic components (Software 1.0) to function operationally. An LLM Agent framework typically consists of core components like Planning (defining future actions), Memory (managing past behaviors), and Tool Use (accessing specific APIs or functions). These foundational components must be defined and managed through reliable, deterministic logic. The design of these agents, therefore, must leverage Software 1.0 distributed systems principles: defined interfaces, fault isolation, and standardized protocols, ensuring that the failure of one probabilistic agent does not cascade through the deterministic system.

A practical example is the Blueprint2Code framework for automated programming, which emulates the human programming workflow through the coordinated interaction of four specialized agents: Previewing, Blueprint, Coding, and Debugging. This closed-loop system uses structured, multi-step process defined by classical logic to ensure the reliability and iterative refinement of the generated code.

C. Advanced Composite AI Use Cases

Real-world enterprise demands rarely fit neatly into a single paradigm, solidifying the need for composite architectures.

Financial Services: Hybrid Fraud Detection Financial fraud detection requires robust, adaptive, and precise systems. Traditional rule-based systems (1.0) struggle with high false positive rates and novel fraud patterns. The required solution is a hybrid architecture that integrates traditional logic with advanced deep learning models (2.0) like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for sequential behavior analysis and Autoencoders for detecting emerging, atypical transaction anomalies. This composite system utilizes a Mixture of Experts (MoE) framework, a piece of Software 1.0 control logic, to dynamically assign predictive responsibility among the experts. Such systems have achieved superior performance, demonstrating high accuracy while supporting regulatory compliance (AML/KYC) by integrating AI as a sophisticated guardian within the financial ecosystem.

Insurance: Intelligent Claims Processing Claims processing is labor-intensive and error-prone. Composite AI addresses this by integrating multiple components: Natural Language Processing (3.0) is used to understand complex claim narratives; Machine Learning (2.0) algorithms are applied to analyze customer data and detect fraudulent patterns (e.g., inconsistencies, red flags); and Rule-Based Systems (1.0) automate high-volume, low-complexity claims processing and ensure adherence to regulatory compliance standards. This blend speeds up the process, reduces operational costs, and minimizes human error.

IV. Engineering for Reliability and Determinism in Software 3.0

The primary challenge in adopting Software 3.0 in the enterprise is mitigating its inherent lack of consistency and reliability: managing its “cognitive deficits”. Architects must deploy advanced engineering techniques to enforce deterministic behavior from probabilistic outputs.

A. The Fine-Tuning vs. Prompting Decision Matrix

Adapting an LLM for a specific business use case typically involves two core methods: prompting and fine-tuning.

- Prompt Engineering (Generalization): This involves giving the model detailed, clear, and descriptive instructions, context, constraints, and desired output formats (e.g., using frameworks like COSTAR: Context, Objective, Style & Tone, Audience, Response). It allows for rapid iteration and leverages the model’s broad general knowledge. However, relying purely on prompting often results in lower consistency and a higher risk of context shifting, making it insufficient for tasks requiring high precision or compliance.

- Fine-Tuning (Specialization): This process goes a step further by training the model with hundreds or thousands of specific examples tailored to the task (e.g., interpreting financial reports). Fine-tuning slightly modifies the model’s base behavior, making it an “expert” in a specialized domain (SW 2.0 principles applied to LMs). This maximizes accuracy, consistency, and stability for specific, narrow tasks. Techniques like LoRA or QLoRA are used for this specialization.

The architectural choice between these methods depends on the required output fidelity. The fundamental technical requirement is iterative measurement. Architects must continuously evaluate whether the desired accuracy, latency, and consistency levels are met by prompting alone, or if the investment in fine-tuning is necessary to stabilize performance. The architectural choice depends on the nature of the model’s performance deficits: deficits in recency or specificity demand RAG (contextual data injection); deficits in consistency or style demand Fine-Tuning (systemic behavior modification).

LLM Adaptation Strategy Matrix

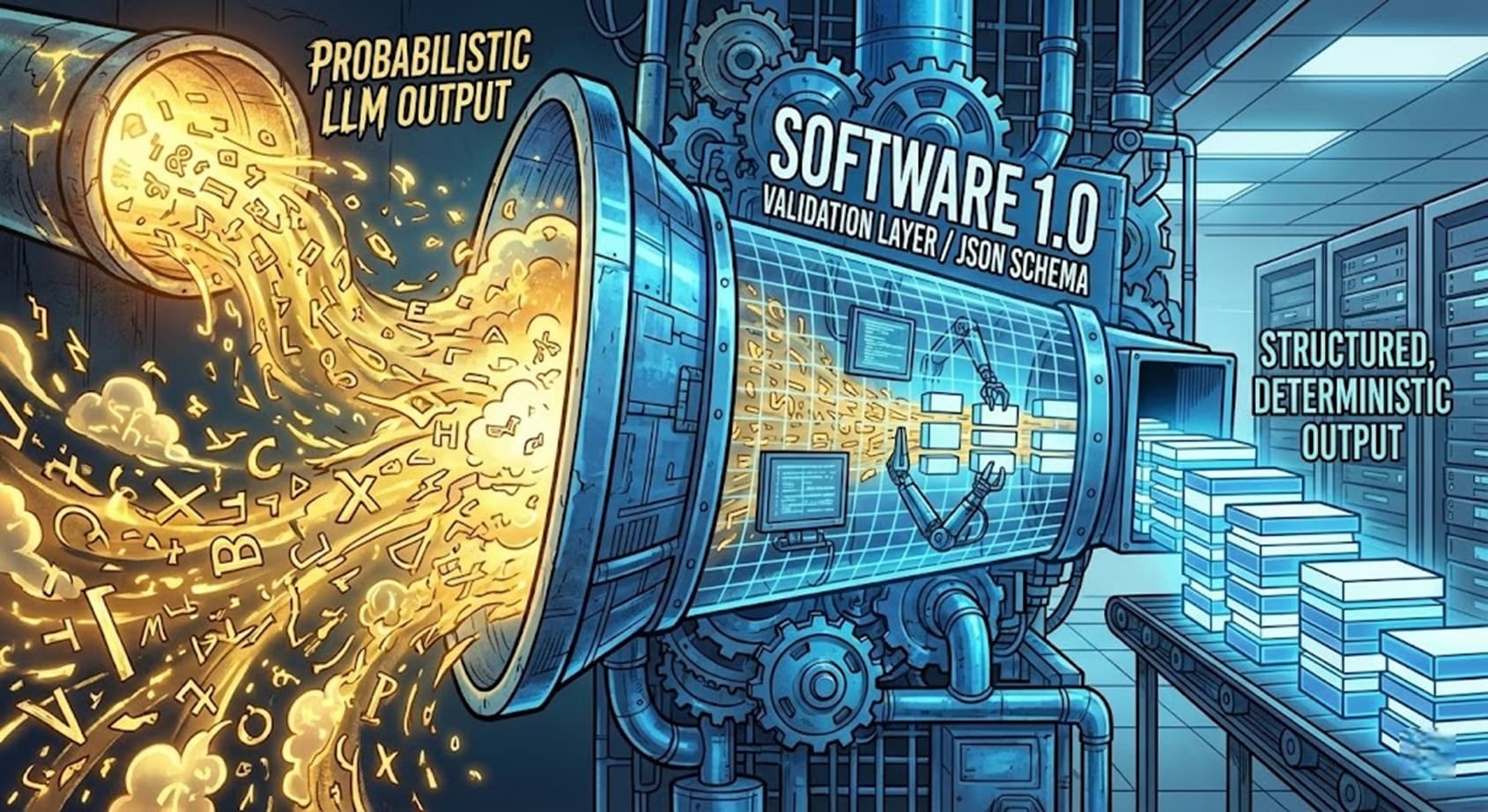

B. Enforcing Predictable Outputs: The Role of Software 1.0 Constructs

For LLMs to function as reliable components within a deterministic enterprise system (e.g., triggering an API call, updating a database), their output cannot be free-form text. The core challenge is that, without intervention, LLMs may produce invalid syntax, violate schema rules, or ignore domain constraints.

Structured Output and Verification Engineering To manage this volatility, architects must aggressively enforce structured output. This is achieved by leveraging Software 1.0 constructs like JSON schemas and data validation libraries (e.g., Pydantic). The process involves defining a precise schema for the desired response and passing this schema to the LLM. Structured outputs are a criminally underused tool for making LLMs programmatically consumable, essentially acting as “neural networks without the training” for tasks like information extraction.

In this context, the prompt might be the high-level instruction (the English code), but the Pydantic schema acts as the architectural contract and the validation mechanism. This technique effectively reintroduces type safety into the probabilistic domain of LLMs. Even with careful prompting, the architecture must include a verification layer (SW 1.0) to validate the output against the defined schema, as the LLM’s output should never be trusted without programmatic verification.

Constrained Decoding and Determinism Advanced systems use Constrained Decoding, a technique that ensures generated outputs adhere to specific, predefined syntactic rules. This is crucial for tasks like code generation or complex response formatting, as it prevents the model from generating invalid syntax or missing required arguments for subsequent API calls. By setting the model’s temperature to zero (or near zero), the model is made more deterministic and less creative, which is precisely what is required when extracting structured data for enterprise workflows.

The architect’s responsibility has broadened to encompass Verification Engineering. This involves building robust systems, relying heavily on traditional Software 1.0 controls and unit tests, that monitor, validate, and sometimes critique the probabilistic outputs of the LLM to prevent non-deterministic behavior from compromising mission-critical processes.

V. Operationalizing AI at Scale: The LLMOps and Governance Framework

The transition of AI solutions from laboratory prototypes to scalable, mission-critical production systems demands robust operational practices, collectively known as MLOps and its specialized extension, LLMOps.

A. From MLOps to LLMOps: New Operational Requirements

LLMOps automates the entire lifecycle of large language models, extending MLOps best practices to account for the scale, complexity, and unique sensitivities of LLMs, particularly their dynamic workloads and acute sensitivity to prompt and data changes.

Prompt Lifecycle Management Since natural language prompts are now a form of code, LLMOps must manage them with the same rigor as traditional source code. This involves comprehensive Prompt Lifecycle Management:

- Versioning and Testing: Prompts must be versioned to maintain a history of changes, similar to code branches. Platforms should allow side-by-side comparison of different prompt variants (A/B testing) to select the highest-performing version for production.

- Integration: Prompts must be embedded directly into applications and integrated into CI/CD pipelines with minimal code changes.

- Security and Guardrails: LLMOps must proactively secure the system against specific Software 3.0 threats, such as Prompt Injection (malicious inputs designed to alter behavior) and Jailbreaking (attempts to bypass safety protocols).

Continuous Monitoring and Maintenance The brittleness of neural networks means that model performance can degrade over time due to drift, inconsistencies, or data changes. Ongoing maintenance is non-negotiable. Continuous monitoring tools are required to detect model drift, data drift, and performance degradation in real-time. This includes automated retraining pipelines, bug fixes, and performance enhancements based on new data infusions and real user feedback.

B. Data Governance and Compliance in the AI Lifecycle

Effective data governance is an essential precursor to scalable AI adoption, providing the principles, practices, and tools needed to manage an organization’s data assets throughout their entire lifecycle: from processing and storage to security and accessibility.

Securing RAG in Hybrid Environments The RAG pipeline is particularly exposed to security risks because it handles sensitive data at every stage: ingestion, chunking, embedding, vector storage, retrieval, and generation. Securing these complex, multi-stage systems across hybrid cloud and on-premises environments requires consistent, strong controls.

Key governance actions include:

- Enforcing Protection Policies: Consistent use of tokenization, masking, and encryption across all environments.

- Vector Database Security: Protecting the vector databases and the resulting embeddings, which store vectorized representations of proprietary knowledge.

- Auditability and Provenance: Governance frameworks must enable Provenance Tracking, which tracks the origin and history of data used in the knowledge graph or vector store. This ensures trust and auditability, allowing organizations to maintain compliance and avoid data sovereignty failures and privacy risks.

This commitment to Software 1.0 governance principles provides the necessary Trust Infrastructure for scaling probabilistic AI systems.

C. Economic Optimization of Hybrid Architectures (A FinOps Perspective)

The massive computational power and memory required for running large models necessitate that architects also act as financial optimizers. The goal is not merely cost reduction but designing a smarter, proactive architecture that scales efficiently with business demands.

Hybrid Cloud Architecture Leading enterprises are abandoning the binary choice of cloud-versus-on-premises and are instead building hybrid architectures. This allows organizations to leverage the elasticity and scale of public cloud platforms while maintaining critical on-premises infrastructure for data sovereignty, specific hardware needs, or legacy systems. Managing costs across this complex environment is challenging for FinOps teams.

AI-Driven Cost Management

A. The Shift: From Manual Coder to Intelligent Orchestrator

The integration of AI-powered tools has automated routine coding tasks, bug fixes, and testing functions. Developers are moving from the manual creation of logic (Software 1.0) to becoming coordinators of AI-driven development ecosystems. Future architects will coordinate complex AI workflows, rather than manually implementing every line of code. This transformative role requires a deep understanding of how to manage transparency, address ethical implications, and ensure effective collaboration between human teams and AI systems, a process often accelerated through digital mentoring and transformation.

The developers who thrive in this environment are those who master the necessary combination of competencies, viewing the tripartite paradigm not as separate technologies but as complementary programming tools for system design.

B. The New Skill Matrix for Software 3.0 Architects

The transition demands a fusion of deep technical knowledge across all three software eras, defining a new set of critical competencies for the AI Architect:

The New Skill Matrix for the AI Architect

C. Conclusion and Recommendations for Executive Leadership

The data overwhelmingly supports the necessity of a Composite AI architectural approach. The evolution of software does not represent a replacement cycle but rather an expansion of the builder’s toolkit. To successfully deploy AI solutions at an enterprise level, leaders must adopt the following strategic conclusions and recommendations:

- Mandate Composite Architecture (SW 1.0 + 2.0 + 3.0): Treat Classical Code, Neural Networks, and LLMs as complementary programming languages. Solutions must be designed to prioritize Software 1.0 for control flow, security, and deterministic execution; Software 2.0 (specialized ML/SLMs) for low-latency, specialized prediction and classification; and Software 3.0 for context interpretation, content generation, and high-level orchestration. The Software 1.0 layer must function as the indispensable deterministic wrapper around the probabilistic core.

- Institutionalize LLMOps and Prompt Governance: Recognize that prompts are the new source code for Software 3.0, and they require rigorous management. Immediate investment in LLMOps infrastructure for prompt versioning, continuous output monitoring, and structured output enforcement (Pydantic/Constrained Decoding) is required. Furthermore, framing data governance, provenance tracking, and RAG security as essential Trust Infrastructure will ensure the reliability and auditability necessary for high-stakes, regulated environments.

- Cultivate Hybrid Talent: Shift talent strategy to prioritize architects fluent across all three programming stacks. The most valuable professionals are those capable of applying Systems Thinking to decompose complex tasks into resilient, cognitive microservices (A2A), designing effective context environments, and building robust verification engineering layers to ensure the system works reliably despite the non-deterministic nature of the underlying models.

- Prioritize Economic Optimization in Design: Adopt a FinOps strategy driven by AI. Move beyond monolithic, large-model reliance by actively designing the Computational Inference Strategy (CIS). This involves strategically using smaller, specialized models or employing verification techniques (voting, self-correction) powered by classical logic to achieve the optimal balance of accuracy, latency, and cost efficiency for every individual workflow.

Give your network a competitive edge in Enterprise Architecture.

Establish your authority. Amplify these insights with your professional network.

Continue Reading

Hand-picked insights to expand your understanding of the evolving AI landscape.